A leading member of the Kurdish Coalition, parliamentarian Mahmoud Othman, said that his list had come out in support of Nouri al-Maliki’s second term as prime minister. His statement came after a round table meeting in the Kurdish capital of Irbil that included representatives of most of Iraq’s major blocs that occurred on October 27, 2010.

According to Roads To Iraq the Kurdish Coalition and Maliki’s State of Law agreed to a number of points in forming the new government. A Sunni member of Iyad Allawi’s Iraqi National Movement would be given the speaker of parliament, Allawi himself would get a high office, and Maliki would return as premier. Allawi was pressured to accept this deal by leading members of his list including the head of the Iraqi National Dialogue Front Saleh al-Mutlaq, parliamentarian Osama Nujafi who is the brother of Ninewa’s governor Atheel Nujafi that heads the Al-Hadbaa party there, deputy Prime Minister Rafi Issawi, and current Vice President Tariq Hashemi.

There have been reports of the National Movement’s change in position. A member of the list told Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty on the day of the Irbil meeting that his coalition had dropped its objections to Maliki staying in office. He claimed that Allawi was willing to bend over forming a ruling coalition, and didn’t want to drag out the process anymore.

The problem now appears to be Maliki and Allawi coming to a power-sharing agreement. The National Movement is allegedly asking for a committee to go through all the laws passed by Maliki since the March 2010 election, the presidency for Allawi, and no objections to their choices for ministers. State of Law is said to reject all those demands saying that no committee has the authority to review ratified laws, and that the National Movement will be denied any security positions. The Kurds are also asking for current President Jalal Talabani to keep his job. On the other hand, they are demanding a national unity government that includes Allawi.

Whether this was just the latest unfounded rumor floating around Iraq or if there really was a breakthrough in Irbil is unknown. The Kurds, as the largest uncommitted bloc left in parliament, do hold the future of the premiership in their hands. Whoever they pick, will become Iraq’s leader. After Moqtada al-Sadr decided to support Maliki earlier in October, momentum shifted in the premier’s favor. Allawi’s inability to draw any major parties to his side besides the Supreme Islamic Iraqi Council and Fadhila parties that only hold fifteen seats between them, seemed to seal his fate. It seems likely then that the Kurds will eventually support Maliki, and then together they will try to bring Allawi into a national unity government as the next step whether that happened in the Irbil meeting or not.

SOURCES

Al-Jaff, Wissam, “Iraqi Shiites bloc prepare to participate in Erbil meeting,” AK News, 10/27/10

Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, “Key Iraqi Bloc Signals Readiness To Compromise In Coalition Talks,” 10/27/10

Al-Rafidayn, Al-Zaman, Alsumaria TV, “Kurds Support Al-Maliki, Urge Al-Iraqiya to Join National Partnership Government,” MEMRI Blog, 10/28/10

Roads To Iraq, “The “Round-Table” results,” 10/28/10

Saturday, October 30, 2010

Friday, October 29, 2010

Sadr’s Conditional Support For Maliki

On October 18, 2010 Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki made his latest trip to Iran. There he met with top leaders in Tehran as well as traveling to Qom to see Moqtada al-Sadr. This was the first time the two had met face to face in several years since Sadr originally put Maliki in office. On October 1, the Sadrists made an about face and went from one of the premier’s greatest critics, to his most important supporters. Sadr’s support appears to be conditional however.

There are reports that the Sadrists have demanded that Maliki include Iyad Allawi’s Iraqi National Movement and the Supreme Islamic Iraqi Council (SIIC) in any new ruling coalition. They’ve also said that they won’t stand in the way if Vice President Adel Abdul Mahdi of the Supreme Council is able to put together a majority in parliament to become prime minister. The National Movement has come out in support of Mahdi.

Including Allawi and the SIIC will not be easy for Maliki. The two are trying to put together a rival coalition to keep Maliki out of power. The National Movement has consistently said that only they have the right to form a new government because they won the most seats in the March 2010 election. The SIIC on the other hand, has lost most of its popular support, but is attempting to hold onto its influence by pushing Mahdi for the top job in Iraq. The Kurds hold the fate of both Maliki and Mahdi as the largest uncommitted bloc left. Whoever they choose will be the next leader of the country. If they select Maliki then the SIIC and National Movement will be forced to give up their aspirations, and begin negotiations over their role in the next government because they don’t want to be left out of the spoils. However, it appears if the Kurds choose Mahdi, the Sadrists will go with him because they don’t want to miss out on ministries either.

Sadr and his followers have played their hand well so far in Iraq. They have allegedly been promised seven ministries, and an unknown amount of jobs for coming out for Maliki. They are now pushing their agenda further by demanding that Maliki form a national unity government, while letting him know that if his rivals come up with a ruling coalition they will go with them instead. By setting further conditions, the Sadrists hope to not only get concessions, but also be a real power player in Iraqi politics.

SOURCES

Alsumaria, “Al Maliki meets Al Sadr in Iran,” 10/19/10

Chulov, Martin, “How Iran brokered a secret deal to put its ally in power in Iraq,” Guardian, 10/17/10

Erdbrink, Thomas and Fadel, Leila, “Maliki meets with Iranian leaders in Tehran,” Washington Post, 10/18/10

MEMRI Staff, “Conflicting Reports on the Premiership in Iraq,” MEMRI Blog, 10/20/10

There are reports that the Sadrists have demanded that Maliki include Iyad Allawi’s Iraqi National Movement and the Supreme Islamic Iraqi Council (SIIC) in any new ruling coalition. They’ve also said that they won’t stand in the way if Vice President Adel Abdul Mahdi of the Supreme Council is able to put together a majority in parliament to become prime minister. The National Movement has come out in support of Mahdi.

Including Allawi and the SIIC will not be easy for Maliki. The two are trying to put together a rival coalition to keep Maliki out of power. The National Movement has consistently said that only they have the right to form a new government because they won the most seats in the March 2010 election. The SIIC on the other hand, has lost most of its popular support, but is attempting to hold onto its influence by pushing Mahdi for the top job in Iraq. The Kurds hold the fate of both Maliki and Mahdi as the largest uncommitted bloc left. Whoever they choose will be the next leader of the country. If they select Maliki then the SIIC and National Movement will be forced to give up their aspirations, and begin negotiations over their role in the next government because they don’t want to be left out of the spoils. However, it appears if the Kurds choose Mahdi, the Sadrists will go with him because they don’t want to miss out on ministries either.

Sadr and his followers have played their hand well so far in Iraq. They have allegedly been promised seven ministries, and an unknown amount of jobs for coming out for Maliki. They are now pushing their agenda further by demanding that Maliki form a national unity government, while letting him know that if his rivals come up with a ruling coalition they will go with them instead. By setting further conditions, the Sadrists hope to not only get concessions, but also be a real power player in Iraqi politics.

SOURCES

Alsumaria, “Al Maliki meets Al Sadr in Iran,” 10/19/10

Chulov, Martin, “How Iran brokered a secret deal to put its ally in power in Iraq,” Guardian, 10/17/10

Erdbrink, Thomas and Fadel, Leila, “Maliki meets with Iranian leaders in Tehran,” Washington Post, 10/18/10

MEMRI Staff, “Conflicting Reports on the Premiership in Iraq,” MEMRI Blog, 10/20/10

Thursday, October 28, 2010

Kurdistan Signs New Oil Deal With U.S. Firm

|

| Irbil Province Where Marathon Will Be Working Source: Wikimedia |

The terms agreed upon are like others the Natural Resource Ministry has offered for petroleum development with Marathon getting a 20 year production sharing contract with an option to extend it for another five years. Production sharing agreements allow the companies to claim the fields’ reserves on their own books and share in the profits. Those types of contracts are common when looking for new oil finds such as in Kurdistan because the work can be costly and the returns low.

Marathon signed under the KRG’s 2007 oil law, which Baghdad does not recognize. An adviser to the Resource Ministry said that the Oil Ministry has always objected to their deals, but they don’t care because they have their own petroleum legislation. The KRG has been inking contracts with foreign petroleum companies since 2003. It claims that it has the right to develop its own resources independently of the central government. That has been hotly disputed by the Oil Ministry, especially under current Minister Hussein Shahristani who has called all of the Kurdish contracts illegal. The central government has also banned any company working in the region from signing deals for the much larger southern oil fields. That has been enough to deter major corporations from signing with the Kurds. Marathon is the first exception. Overall, the KRG is estimated to have around 13% of Iraq’s proven reserves. Only two fields, Tawke and Taq Taq, actually produce petroleum today. Marathon may be hoping that the central and regional governments will come to some type of agreement over oil in the new regime that will make their deal worthwhile. The Kurdish parties have made recognition of their petroleum contracts a major demand in their negotiations over joining any ruling coalition.

Foreign Oil Firms Operating In Kurdistan

2003-2010

A&T Petroleum, Turkey

Addax Petroleum, Canada/Switzerland

Aspect Energy, U.S.

Crescent Petroleum, UAE

Dana Gas, UAE

DNO, Norway

Genel Enerji, Turkey

Groundstar Resources, Canada

Gulf Keystone Petroleum, U.K.

Heritage Oil and Gas, Canada

Hillwood International Energy, U.S.

Hunt Oil, U.S.

Kalegran/MOL, Hungary

Korea National Oil Corporation, South Korea

Marathon, U.S.

Niko Resources, Canada

Norbest, Russia

Oil Search, Australian

OMV Petroleum Exploration, Austria

Perenco, France

Pet Oil, Turkey

Prime Natural Resources, U.S.

Reliance Energy, India

Sinopec, China

Sterling Energy International, U.S.

Talisman Energy, Canada

Texas Keystone, U.S.

Vast Exploration, Canada

Western Zagros, Canada

SOURCES

International Crisis Group, “Iraq After The Surge II: The Need for a New Political Strategy,” 4/30/08

- “Oil For Soil: Toward A Grand Bargain On Iraq And The Kurds,” 10/28/08

Saifaddin, Dilshad, “Kurdistan signed four new deals for oil production,” AK News, 10/22/10

UPI, “Marathon land first oil deals in Iraq,” 10/21/10

Turkey’s Genel Enerji Plans To Sell Portion Of Its Oil Holdings In Kurdistan To Expand Work There

Tawke oil field which Turkey's Gene Enerji owns a percentage of

Source: Reuters

Source: Reuters

As reported before, Turkey’s Genel Enerji contacted JP Morgan Chase in August 2010 to sell all or part of its shares in oil fields in the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG). The full details have now come out. Genel Enerji plans on selling stakes in three Kurdish fields to South Korean’s UI Energy for $175 million. The Turkish firm will sell 5% of its 40% stake in the Dohuk field in the province of the same name, 5% of its 25% share in the Tawke field also in Dohuk, and 10% of its 25% portion of the Miran field in Sulaymaniya. Miran is jointly run with England Heritage Oil, while Tawke and Dohuk are managed by Norway’s DNO.

Genel plans on using the profits from the sale to expand its operations in the KRG. It wants to increase production at Tawke from 30,000 barrels a day currently to 60,000 barrels, and boost the Taq Taq field in Irbil, which it is a part owner in along with Addax International, China’s Sinopec, and the KRG, from 60,000 barrels a day to 180,000. Those two are the only fields in the region currently producing oil. The petroleum is used for domestic uses and sold illegally to Iran. It also wants to construct a pipeline from the Taq Taq field to Iraq’s northern line that flows to Turkey, and to conduct exploratory drilling in Kurdistan. All together it estimates that these efforts will cost between $800-$900 million over the next two years.

In mid-2009 the Kurds were allowed to export oil from the Taq Taq and Tawke fields. That quickly ended as the KRG and Baghdad could not agree upon who would pay Genel Enerji and the other foreign operators. Kurdistan, Genel, and others are hoping that a deal will be worked out after a new Iraqi government is formed, as the Kurdish parties have made it one of their demands in joining any new ruling coalition. Genel is betting that the Kurds will be successful, which is why they are going ahead with this sale and expansion plans.

SOURCES

Bloomberg, “Genel Enerji sells northern Iraq oil stakes,” 10/17/10

Gwertzman, Bernard, “Iraq’s Impasse and ‘Confusing’ Politics,” Council on Foreign Relations, 10/6/10

Stigset, Marianne, “DNO Chief Expects Increased Business in Iraq’s Kurdish Region,” Bloomberg, 8/18/10

Wednesday, October 27, 2010

Iraq Ranked Fourth Most Corrupt Country In World

On October 26, 2010 Germany’s Transparency International released its 2010 Corruption Index. This year’s survey included 178 countries. Each nation was given a rank from highly corrupt 0 to highly clean 10 based upon different sources. For the second year in a row Iraq was ranked the fourth most corrupt country in the world. It received a score of 1.5. Somalia was the most corrupt at 1.1. Myanmar and Afghanistan were tied for second with a score of 1.4.

Since the 2003 invasion Iraq has slipped farther and farther down the Corruption Index. In 2003 Iraq was number 20. It went down to number 17 in 2005, up to 22 in 2005, and then fell all the way to number three in 2006. 2007 Iraq received its worst ranking at number two. It then rose to number three in 2008, and has stayed at number four this year and last.

Iraq’s Ranking In Corruption Index 2003-2010

2003 #20

2004 #17

2005 #22

2006 #3

2007 #2

2008 #3

2009 #4

2010 #4

A review of some of the major corruption stories this year shows why Iraq has such a low ranking. In September 2010 an appeals court dropped the case against former Trade Minister Abdul al-Falah al-Sudani even though it’s believed that $4-$8 billion went missing from his ministry. That was part of the country’s long tradition of not prosecuting any high officials for wrongdoing. In May, three state-run banks made $7.7 billion in illegal, off the book loans to three private banks. In April, Karbala’s provincial council accused the Trade Ministry of buying expired food for the ration system, which is the largest in the world. There’s also the fact that Iraq lacks adequate bookkeeping of its finances, records of most of its petroleum production, and has massive oil smuggling, all of which facilitate and encourage theft, bribery, and fraud. As long as all the major political parties benefit from stealing from the government they run, this sad state of affairs will continue.

SOURCES

Transparency International, “Corruption Perceptions Index 2010,” 10/26/10

Since the 2003 invasion Iraq has slipped farther and farther down the Corruption Index. In 2003 Iraq was number 20. It went down to number 17 in 2005, up to 22 in 2005, and then fell all the way to number three in 2006. 2007 Iraq received its worst ranking at number two. It then rose to number three in 2008, and has stayed at number four this year and last.

Iraq’s Ranking In Corruption Index 2003-2010

2003 #20

2004 #17

2005 #22

2006 #3

2007 #2

2008 #3

2009 #4

2010 #4

A review of some of the major corruption stories this year shows why Iraq has such a low ranking. In September 2010 an appeals court dropped the case against former Trade Minister Abdul al-Falah al-Sudani even though it’s believed that $4-$8 billion went missing from his ministry. That was part of the country’s long tradition of not prosecuting any high officials for wrongdoing. In May, three state-run banks made $7.7 billion in illegal, off the book loans to three private banks. In April, Karbala’s provincial council accused the Trade Ministry of buying expired food for the ration system, which is the largest in the world. There’s also the fact that Iraq lacks adequate bookkeeping of its finances, records of most of its petroleum production, and has massive oil smuggling, all of which facilitate and encourage theft, bribery, and fraud. As long as all the major political parties benefit from stealing from the government they run, this sad state of affairs will continue.

SOURCES

Transparency International, “Corruption Perceptions Index 2010,” 10/26/10

Tuesday, October 26, 2010

Iraq Won’t Say Where Its Money Has Gone

In September 2010 the United States Government Accountability Office (GAO) issued a report that Iraq had built up a $52.1 billion surplus from 2005 to 2009. At the same time Baghdad had accumulated an estimated $40.3 billion in outstanding advances, which left Iraq with $11.8 million in unclaimed funds. That amount was unclear however, since the Board of Supreme Audit, the main financial watchdog within the government, couldn’t account for all of the advances. The GAO couldn’t determine what happened with 40% of the advances since Baghdad wouldn’t provide any details about them. Finally, the state-run banks that hold a large amount of the government’s money didn’t have reliable records either.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) signed an agreement with Baghdad in February to help reform its budgeting, spending, and accounting measures. It too was curious about Iraq’s unspent money after the GAO report, and asked the Finance Ministry to clarify the matter. The IMF gave the ministry until September 30 to explain what the $40.3 billion in advances had been spent on. The Ministry of Finance never responded.

This is just the latest example of how poorly Baghdad keeps its books. Despite its security and political issues, Iraq still has large amounts of money flowing through its coffers due to its oil industry. The problem starts there, as no one knows exactly how much petroleum is produced because of the lack of meters, a weak bureaucracy, theft, and corruption. Once the oil is sold and deposited, the trail gets murkier as the banks lack an efficient book keeping system. When the funds are distributed to the various ministries things get no better because of the paper-based system, the lack of trained and qualified staff, and political appointees. The IMF and United States have been pushing reform for several years now, but progress has been slow and uneven. They can only go as far as the Iraqis allow them, and so far, that’s only been in small increments. Until Baghdad wants real change, its finances will remain a wreck.

SOURCES

Amies, Nick, “Potential oil windfall raises concerns over Iraq’s financial black hole,” Deutsche Welle, 10/11/10

United States Government Accountability Office, “Iraqi-U.S. Cost-Sharing Iraq Has a Cumulative Budget Surplus, Offering the Potential for Further Cost-Sharing,” September 2010

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) signed an agreement with Baghdad in February to help reform its budgeting, spending, and accounting measures. It too was curious about Iraq’s unspent money after the GAO report, and asked the Finance Ministry to clarify the matter. The IMF gave the ministry until September 30 to explain what the $40.3 billion in advances had been spent on. The Ministry of Finance never responded.

This is just the latest example of how poorly Baghdad keeps its books. Despite its security and political issues, Iraq still has large amounts of money flowing through its coffers due to its oil industry. The problem starts there, as no one knows exactly how much petroleum is produced because of the lack of meters, a weak bureaucracy, theft, and corruption. Once the oil is sold and deposited, the trail gets murkier as the banks lack an efficient book keeping system. When the funds are distributed to the various ministries things get no better because of the paper-based system, the lack of trained and qualified staff, and political appointees. The IMF and United States have been pushing reform for several years now, but progress has been slow and uneven. They can only go as far as the Iraqis allow them, and so far, that’s only been in small increments. Until Baghdad wants real change, its finances will remain a wreck.

SOURCES

Amies, Nick, “Potential oil windfall raises concerns over Iraq’s financial black hole,” Deutsche Welle, 10/11/10

United States Government Accountability Office, “Iraqi-U.S. Cost-Sharing Iraq Has a Cumulative Budget Surplus, Offering the Potential for Further Cost-Sharing,” September 2010

Monday, October 25, 2010

AL JAZEERA VIDEO: Maliki's Secret Police Forces, Sadrist Assassination Attempts Against Maliki/Allawi

SOURCE

Carlstrom, Gregg, "Nouri al-Maliki's 'detention squad,'" Al Jazeera, 10/24/10

Iraq’s Political Parties Try To Play The Torture Card With Maliki

After WikiLeaks released its cache of U.S. military war logs, Iraq’s political parties were quick to put them to work in their internal struggle to form a new Iraqi government. Iyad Allawi’s Iraqi National Movement said that the documents gave proof that Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki should not stay in office. They claimed that under his rule Iraqi security forces tortured prisoners, and that was a sign of Maliki’s abuse of power. They went on to say that having all the decision-making and security forces in the hands of one man was what led to the mistreatment in Iraqi prisons. In response, the prime minister’s office issued a statement saying that the timing of the WikiLeaks release might have been politically motivated, and that there was no proof of abuses under Maliki’s rule. The problem with playing this card is that almost all of the parties that have been involved in the government have committed acts of torture.

When Allawi was named the interim prime minister in January 2005 he focused upon security, and using an iron fist against the insurgency. The premier quickly played off a rumor that he shot and killed a prisoner in a Baghdad police station. In the next few months, the Human Rights Watch, the State Department and U.S. military units recorded human rights abuses by the Allawi government. In January 2005 Human Rights Watch reported misconduct by the Iraqi intelligence services and police forces. The organization said that abuses had become routine, and found no effort by Baghdad to stop it. In March the Department of State issued its annual human rights paper that recorded rape, torture, and illegal detention in Iraq. The next month, the senior tactical commander in Iraq ordered American forces to prevent any abuses by Iraqis, and in May the overall U.S. commander General George Casey sent a letter to the troops saying that they needed to make sure Iraqi forces treated detainees correctly. This came as a result of increasing reports by U.S. units of human rights violations by Iraqis. The 1st Cavalry Division collected more than 100 allegations of abuses by Iraqi police and soldiers over a six-month period that included beatings, electric shock, and choking, while the 3rd Infantry Division received 28 more allegations.

The Supreme Council’s militia, the Badr Brigade, was implicated in abuses through its control of local police forces after the invasion, and during its control of the Interior Ministry from April 2005 to May 2006 under Ibrahim al-Jaafari’s premiership. As early as 2003 the British recorded a special police force in Basra run by Badr members who were tracking down former Baathists and holding them in secret prisons in the city. Under Prime Minister Jaafari, Bayan Jabr, a Badr Brigade commander, was made Interior Minister. U.S. soldiers would later find a secret prison run by the Ministry in Baghdad in November 2005 that held 169 prisoners, most of which had been tortured. Jabr denied any wrongdoing. Today Jabr is the acting Finance Minister in Maliki’s government.

The two ruling Kurdish parties, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) have been implicated in prison abuse since the 1990s. Each party has its own security force and intelligence agency that have been involved in running secret prisons, arresting not only terrorist suspects, but legitimate political opponents as well, and committing acts of torture. In September 2010 for example, Amnesty International came out with a report that noted that Kurdistan not only held suspected Islamist insurgents belonging to Ansar al-Islam, but also members of the legal Kurdistan Islamic Movement and Kurdistan Islamic Group political parties. Many of them were being held without trial because the authorities would rather have them stay in prison than go through the legal process.

Widespread abuse has also happened under Maliki’s rule. Human Rights Watch, the Interior and Human Rights Ministries, the State Department, and Amnesty International have all documented torture, disappearances, secret prisons, arbitrary arrests, overcrowded detention facilities, and torture by Iraqi forces since Maliki took power in 2006. In April 2010 for example, a secret prison was revealed in the Muthanna airport in Baghdad that was directly under the control of the prime minister’s office. The prison held hundreds of Sunni prisoners arrested in Ninewa province, most of which had been abused. Investigations of that incident and all others under Maliki have largely gone nowhere, with no senior official ever being held accountable.

Torture is common in the Middle East, but Iraq stands out because it has so many prisoners due to the on-going insurgency. Almost all of the major parties that have ruled Iraq since it got back its sovereignty in 2005 have been involved in these abuses. Some like the SIIC’s Badr Brigade have carried out sectarian and revenge attacks upon former Baathists and Sunnis. Others like the Kurdish PUK and KDP have clamped down on Islamic insurgents and opposition parties. Under Maliki, the security forces have carried on long-standing practices of beating and torturing suspects to get a confession out of them, as well as being accused of sectarian biases. The WikiLeaks papers document several specific cases of abuse by Iraqi police and soldiers from 2005 to 2009. Using them for political purposes in the struggle over forming a new Iraqi government could’ve been expected, but was not a smart move. Maliki is definitely implicated in abuses, but so are his accusers.

SOURCES

Agence France Presse, “Iraq probes torture complaints,” 6/7/09

Amnesty International, “Hope and Fear, Human rights in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq,” April 2009

- “New order, same abuses: Unlawful detentions and torture in Iraq,” September 2010

Anderson, Jon Lee, “A Man Of The Shadows,” New Yorker, 1/24/05

Associated Press, “Iraqi PM on the defense in WikiLeaks release,” 10/23/10

Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, And Labor, “2009 Human Rights Report: Iraq,” U.S. State Department, 3/11/10

Fuller, Max, “State-Sanctioned Paramilitary Terror in Basra Under British Occupation,” Global Research, 8/8/08

Graham, Bradley, “Iraqi police accused of abuses,” San Francisco Chronicle, 5/20/05

Human Rights Watch, “The Quality of Justice, Failings of Iraq’s Central Criminal Court,” December 2008

Knowlton, Brian, “U.S. alleges rights abuses by Iraqis,” San Francisco Chronicle, 3/1/05

Miller, Greg and Finn, Peter, “Secret Iraq war files offer grim new details,” Washington Post, 10/23/10

Perito, Robert and Kristoff, Madeline, “Iraq’s Interior Ministry: The Key To Police Reform,” United States Institute of Peace, July 2009

Sengupta, Kim, “Secret Iraqi government prison was ‘worse than Abu Ghraib,’” The Independent, 4/29/10

When Allawi was named the interim prime minister in January 2005 he focused upon security, and using an iron fist against the insurgency. The premier quickly played off a rumor that he shot and killed a prisoner in a Baghdad police station. In the next few months, the Human Rights Watch, the State Department and U.S. military units recorded human rights abuses by the Allawi government. In January 2005 Human Rights Watch reported misconduct by the Iraqi intelligence services and police forces. The organization said that abuses had become routine, and found no effort by Baghdad to stop it. In March the Department of State issued its annual human rights paper that recorded rape, torture, and illegal detention in Iraq. The next month, the senior tactical commander in Iraq ordered American forces to prevent any abuses by Iraqis, and in May the overall U.S. commander General George Casey sent a letter to the troops saying that they needed to make sure Iraqi forces treated detainees correctly. This came as a result of increasing reports by U.S. units of human rights violations by Iraqis. The 1st Cavalry Division collected more than 100 allegations of abuses by Iraqi police and soldiers over a six-month period that included beatings, electric shock, and choking, while the 3rd Infantry Division received 28 more allegations.

The Supreme Council’s militia, the Badr Brigade, was implicated in abuses through its control of local police forces after the invasion, and during its control of the Interior Ministry from April 2005 to May 2006 under Ibrahim al-Jaafari’s premiership. As early as 2003 the British recorded a special police force in Basra run by Badr members who were tracking down former Baathists and holding them in secret prisons in the city. Under Prime Minister Jaafari, Bayan Jabr, a Badr Brigade commander, was made Interior Minister. U.S. soldiers would later find a secret prison run by the Ministry in Baghdad in November 2005 that held 169 prisoners, most of which had been tortured. Jabr denied any wrongdoing. Today Jabr is the acting Finance Minister in Maliki’s government.

The two ruling Kurdish parties, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) have been implicated in prison abuse since the 1990s. Each party has its own security force and intelligence agency that have been involved in running secret prisons, arresting not only terrorist suspects, but legitimate political opponents as well, and committing acts of torture. In September 2010 for example, Amnesty International came out with a report that noted that Kurdistan not only held suspected Islamist insurgents belonging to Ansar al-Islam, but also members of the legal Kurdistan Islamic Movement and Kurdistan Islamic Group political parties. Many of them were being held without trial because the authorities would rather have them stay in prison than go through the legal process.

Widespread abuse has also happened under Maliki’s rule. Human Rights Watch, the Interior and Human Rights Ministries, the State Department, and Amnesty International have all documented torture, disappearances, secret prisons, arbitrary arrests, overcrowded detention facilities, and torture by Iraqi forces since Maliki took power in 2006. In April 2010 for example, a secret prison was revealed in the Muthanna airport in Baghdad that was directly under the control of the prime minister’s office. The prison held hundreds of Sunni prisoners arrested in Ninewa province, most of which had been abused. Investigations of that incident and all others under Maliki have largely gone nowhere, with no senior official ever being held accountable.

Torture is common in the Middle East, but Iraq stands out because it has so many prisoners due to the on-going insurgency. Almost all of the major parties that have ruled Iraq since it got back its sovereignty in 2005 have been involved in these abuses. Some like the SIIC’s Badr Brigade have carried out sectarian and revenge attacks upon former Baathists and Sunnis. Others like the Kurdish PUK and KDP have clamped down on Islamic insurgents and opposition parties. Under Maliki, the security forces have carried on long-standing practices of beating and torturing suspects to get a confession out of them, as well as being accused of sectarian biases. The WikiLeaks papers document several specific cases of abuse by Iraqi police and soldiers from 2005 to 2009. Using them for political purposes in the struggle over forming a new Iraqi government could’ve been expected, but was not a smart move. Maliki is definitely implicated in abuses, but so are his accusers.

SOURCES

Agence France Presse, “Iraq probes torture complaints,” 6/7/09

Amnesty International, “Hope and Fear, Human rights in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq,” April 2009

- “New order, same abuses: Unlawful detentions and torture in Iraq,” September 2010

Anderson, Jon Lee, “A Man Of The Shadows,” New Yorker, 1/24/05

Associated Press, “Iraqi PM on the defense in WikiLeaks release,” 10/23/10

Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, And Labor, “2009 Human Rights Report: Iraq,” U.S. State Department, 3/11/10

Fuller, Max, “State-Sanctioned Paramilitary Terror in Basra Under British Occupation,” Global Research, 8/8/08

Graham, Bradley, “Iraqi police accused of abuses,” San Francisco Chronicle, 5/20/05

Human Rights Watch, “The Quality of Justice, Failings of Iraq’s Central Criminal Court,” December 2008

Knowlton, Brian, “U.S. alleges rights abuses by Iraqis,” San Francisco Chronicle, 3/1/05

Miller, Greg and Finn, Peter, “Secret Iraq war files offer grim new details,” Washington Post, 10/23/10

Perito, Robert and Kristoff, Madeline, “Iraq’s Interior Ministry: The Key To Police Reform,” United States Institute of Peace, July 2009

Sengupta, Kim, “Secret Iraqi government prison was ‘worse than Abu Ghraib,’” The Independent, 4/29/10

Sunday, October 24, 2010

Latest Controversy Over The Iraqi Census

On October 18, 2010 Iraq’s Planning Minister Ali Baban said that he wanted to remove a question about respondents’ ethnosectarian identity from the census. Baban suggested that the item should be dropped to relieve tension in the country, and because Ninewa requested it. Baban aired the idea at a meeting of the Iraqi cabinet. Kurdish ministers and members of the Kurdish Coalition in the new parliament strongly objected to the idea. A member of the Census Committee in Kurdistan said that removing the identity question was a violation of the Iraqi constitution, and the Kurdish Coalition threatened a boycott if the item was not included.

This is just the latest controversy over the planned census. Originally it was supposed to be conducted in 2007, but because of the lack of security it was postponed until 2009. Complaints about how the poll might affect the disputed territories led it to be delayed until 2010. It was supposed to happen on October 24 this year, but was just pushed back again to December 5 because Ninewa refused to conduct it as long as Kurdish peshmerga were present in the province, and over concerns over Kirkuk. Iyad Allawi’s Iraqi National Movement has also been lobbying to hold off the census as well. Some of its strongest support in the March 2010 election came from Ninewa, Diyala, and Tamim, which is where the disputed territories lay. Arabs and Turkmen in those areas are worried that the census may reveal a Kurdish majority in the disputed areas like Kirkuk, which would allow them to move ahead with annexing them under Article 140 of the constitution. Arabs, Turkmen, and members of the National Movement would like to maintain the status quo at minimum, and reverse Kurdish advances in the territories if possible. These political disputes have held up the implementation of the census for the last two years, and may do it again.

SOURCES

Ahmed, Hevidar, “Minister threatens to resign due to nationality in census forms,” AK News, 10/20/10

Al-Jader, May, “Debating on the census in Iraq,” AK News, 10/20/10

Al Wanan, Jaafar, “Census delay in Iraq costs billions,” AK News, 10/18/10

This is just the latest controversy over the planned census. Originally it was supposed to be conducted in 2007, but because of the lack of security it was postponed until 2009. Complaints about how the poll might affect the disputed territories led it to be delayed until 2010. It was supposed to happen on October 24 this year, but was just pushed back again to December 5 because Ninewa refused to conduct it as long as Kurdish peshmerga were present in the province, and over concerns over Kirkuk. Iyad Allawi’s Iraqi National Movement has also been lobbying to hold off the census as well. Some of its strongest support in the March 2010 election came from Ninewa, Diyala, and Tamim, which is where the disputed territories lay. Arabs and Turkmen in those areas are worried that the census may reveal a Kurdish majority in the disputed areas like Kirkuk, which would allow them to move ahead with annexing them under Article 140 of the constitution. Arabs, Turkmen, and members of the National Movement would like to maintain the status quo at minimum, and reverse Kurdish advances in the territories if possible. These political disputes have held up the implementation of the census for the last two years, and may do it again.

SOURCES

Ahmed, Hevidar, “Minister threatens to resign due to nationality in census forms,” AK News, 10/20/10

Al-Jader, May, “Debating on the census in Iraq,” AK News, 10/20/10

Al Wanan, Jaafar, “Census delay in Iraq costs billions,” AK News, 10/18/10

Iraq’s Oil Exports Return To 2 Million Barrels A Day

Iraq’s Oil Marketing Organization announced that petroleum exports returned to over 2 million barrels a day in September. The Marketing Organization claimed that last month Iraq exported 2.021 million barrels a day. That was up from 1.788 million barrels a day in August and 1.820 million barrels in July. Basra continued to be the workhorse of Iraq’s oil industry carrying an average of 1.508 million barrels a day, compared to only 513,000 barrels shipped to Turkey through the northern line, and 10,000 barrels trucked to Jordan a day. The Marketing Organization also noted that one reason for the increased foreign sales was surplus oil that was stored in Turkey that was finally released. That probably meant actual production and exports weren’t as high as reported. The State Department for example, reported that overall production only increased to 2.35 million barrels a day in September, up from 2.32 million in August and 2.30 million in July, while exports averaged 1.95 million barrels a day in September. If true, that would mean last month had the second highest export mark since February when Iraq sold 2.05 million barrels a day.

September follows the post-2003 up and down pattern in Iraqi petroleum exports. In January 2009 for example, Iraq sold an average of 1.91 million barrels a day. Then exports declined before climbing back up to 2.04 million barrels in July, followed by another dip until returning to 2.05 million barrels in February 2010. It took another seven months for exports to go back up to 2 million barrels in September. The head of the State Oil Marketing Organization stated that he expected the country to consistently average over 2 million barrels by the end of 2011 because of the new oil deals it signed with foreign companies. The problem as ever is Iraq’s aging infrastructure, weather, bottlenecks, and attacks upon the northern pipeline. The Oil Ministry has plans to address these issues, but until those come to fruition, the petroleum fields can increase production, but the country won’t have the capacity to sell more.

SOURCES

Bureau of Near Eastern Affairs, “Iraq Status Report,” U.S. Department of State, 10/6/10

Reuters, “Iraq oil exports soar to over 2 million bpd,” 10/5/10

Friday, October 22, 2010

Iraq Successfully Auctions Off Three Gas Fields

Representative of Kuwait Energy bids during Iraq’s gas auction

Source: Iraq Oil Report

Source: Iraq Oil Report

Iraq’s Oil Ministry held its auction for three natural gas fields in Baghdad on October 20, 2010. The proceedings were presided over by Oil Minister Hussein Shahristani. The event didn’t garner as many foreign energy companies as Iraq was hoping for, and less than half of the participants placed bids, but at the end of the day all three fields were successfully auctioned off.

The natural gas fields involved in the auction were Akkas, Mansuriyah, and Siba. Akkas is in Anbar province, Mansuriyah in Diyala, and Siba in Basra. Together the three have an estimated reserve of 11.2 trillion cubic feet of gas, which is around 10% of the country’s total. 45 companies that took part in the two oil auctions last year were pre-qualified to participate in this event, but only 13 ended up paying the participation fees. Those were France’s Total, Italy’s Eni, Edison, Norway’s Statoil, Kazakhstan’s KazMunai Gas, Turkey’s TPAO, Japan’s Oil, Gas and Metals National Corporation, Itochu Corp., Mitsubishi, Kuwait Energy, India’s Oil and Natural Gas Corp., South Korea’s KOGAS, TNK-BP, and BP PLC’s Russian joint venture. Of those, only five made bids. The winners will be awarded 20-year service agreements where they will form a joint venture with an Oil Ministry controlled business, paid a flat fee until they reach their production mark, and then paid for extra output after that level is met.

A consortium of TPAO, Kuwait Energy and KOGAS won the Mansuriyah field. Mansuriyah has a reserve of 4.5 trillion cubic feet of gas, and the companies at first offered to produce 320 million cubic feet of gas per day, and asked for $10 per barrel equivalent in extra gas output. The Oil Ministry countered by offering $7 per barrel equivalent, which the consortium ended up accepting.

Kuwait Energy and TPAO also successfully bid on the Siba field in Basra. They promised to produce 100 million cubic feet of gas per day, and be paid $7.50 per barrel equivalent in extra production. They beat out Kazakhstan’s KazMunai Gas that offered to raise output to 60 million cubic feet per day and wanted $16 per extra barrel equivalent of gas production.

Finally, KOGAS and KazMunai beat out Total and TPAO for the Akkas field. KOGAS-KazMunai offered $5.50 per barrel equivalent with a production level of 400 million cubic feet. That was superior to Total-TPAO’s bid of $19 per barrel equivalent and 375 million cubic feet per day.

It appeared that the Oil Ministry’s last minute adjustments to their terms worked out in the end. In the last several weeks the Ministry made a series of concessions to try to get more interest in the auction. That included dropping requirements that companies find a partner for 50% of their exports, reducing signature bonuses, and cutting a fee that businesses would have to pay to train Iraqis in the industry.

Baghdad now has its real work cut out for itself. Iraq lacks any real natural gas network in the country, pipelines to export, or deals with foreign customers to sell to. The government’s first concern is to deliver the gas produced to power plants and other domestic industries. It has promised to build pipelines to accomplish that, but they’re not due to be finished until 2014. It will then need to negotiate with neighboring countries for export lines and long-term delivery contracts. Only when that’s accomplished can this auction really be labeled a success, and Iraq can be said to finally be developing this resource.

SOURCES

Aswat al-Iraq, “Turkish-led consortium wins third Iraq gas field,” 10/20/10

Salaheddin, Sinan, “Iraq gas auction fizzles despite hopes,” Associated Press, 10/20/10

Iraq Attempting To Privatize Its State-Run Businesses Once Again

At the end of September 2010 Iraq’s Industry Ministry offered up ten state-run factories for investment. Foreign companies were offered 15-year production sharing agreements mainly in cement, petrochemical, steel, and pharmaceutical businesses. The Industry Ministry owns 60 firms altogether that control 250 plants. It’s hoping to privatize all of them by 2020. That seems highly unlikely.

The Industry Ministry has tried to privatize before with few results. In March 2010 for example, the Ministry said that it was going to auction off all 250 plants it runs. That was at least the third time it had made such an announcement. So far, only five deals have been reported since 2003. In 2009 it signed a contract for the North Fertilizer Company in Baiji, Salahaddin with Japan’s Marubeni Corp. The Deputy Industry Ministry claims production has increased 30% since then. In April 2010 Baghdad also cut a deal with Larfarge SA, the world’s largest cement producer. Negotiations over other companies were started, but never finalized.

Investing in Iraq’s state-run businesses faces a series of major challenges. One is that they employ thousands of unnecessary workers to keep the unemployment rate down in the country. A consultant to the Central Bank of Iraq for example, told Azzaman in September that 90% of the public employees didn’t deserve their jobs. The government is unwilling to let many of these workers go however, out of fear that they might join militant groups or lead to social unrest. At the same time keeping all those workers makes the companies highly unproductive and expensive to run. Baghdad has even offered subsidies in some cases to keep people working at factories that were up for privatization. Iraq also has very few tariffs to protect their domestic industries at a time when the country is being flooded with cheap imports, the investment laws are obtuse, contradictory, and hard to decipher, and corruption adds extra costs. Finally, the government has arbitrarily taxed and attempted to change deals with foreign companies in the past.

Today, Baghdad wants foreign investment, but is afraid of some of the consequences of privatization. Probably only the most attractive firms the Industry Ministry owns will attract foreign interest. The rest can be kept open as a costly, and inefficient jobs program, or they can be closed, which will increase unemployment, and could lead to instability. That makes deciding the fate of the state-run businesses a difficult one for the government. There are already some pressures from within the Maliki administration against the excessive number of public employees. Still, with billions of extra dollars expected to flow into Baghdad’s coffers with the recently signed oil deals, officials may just take the easy route and keep many of these businesses running rather than suffer the consequences of shutting them down. Which way Baghdad goes will be decided by the next regime, and could be a telling event as to whether Iraq is heading towards a more market oriented economy, or will maintain its state-run system.

SOURCES

Chaudhry, Serena, “U.S. firms say Iraqi regulation a challenge to trade,” Reuters, 10/5/10

Department of Defense, “Measuring Stability and Security in Iraq June 2010,” 9/7/10

Razzouk, Nayla, “Iraq to Offer Tenders to Revamp 250 State Industrial Plants, Official Says,” Bloomberg, 9/28/10

The Industry Ministry has tried to privatize before with few results. In March 2010 for example, the Ministry said that it was going to auction off all 250 plants it runs. That was at least the third time it had made such an announcement. So far, only five deals have been reported since 2003. In 2009 it signed a contract for the North Fertilizer Company in Baiji, Salahaddin with Japan’s Marubeni Corp. The Deputy Industry Ministry claims production has increased 30% since then. In April 2010 Baghdad also cut a deal with Larfarge SA, the world’s largest cement producer. Negotiations over other companies were started, but never finalized.

Investing in Iraq’s state-run businesses faces a series of major challenges. One is that they employ thousands of unnecessary workers to keep the unemployment rate down in the country. A consultant to the Central Bank of Iraq for example, told Azzaman in September that 90% of the public employees didn’t deserve their jobs. The government is unwilling to let many of these workers go however, out of fear that they might join militant groups or lead to social unrest. At the same time keeping all those workers makes the companies highly unproductive and expensive to run. Baghdad has even offered subsidies in some cases to keep people working at factories that were up for privatization. Iraq also has very few tariffs to protect their domestic industries at a time when the country is being flooded with cheap imports, the investment laws are obtuse, contradictory, and hard to decipher, and corruption adds extra costs. Finally, the government has arbitrarily taxed and attempted to change deals with foreign companies in the past.

Today, Baghdad wants foreign investment, but is afraid of some of the consequences of privatization. Probably only the most attractive firms the Industry Ministry owns will attract foreign interest. The rest can be kept open as a costly, and inefficient jobs program, or they can be closed, which will increase unemployment, and could lead to instability. That makes deciding the fate of the state-run businesses a difficult one for the government. There are already some pressures from within the Maliki administration against the excessive number of public employees. Still, with billions of extra dollars expected to flow into Baghdad’s coffers with the recently signed oil deals, officials may just take the easy route and keep many of these businesses running rather than suffer the consequences of shutting them down. Which way Baghdad goes will be decided by the next regime, and could be a telling event as to whether Iraq is heading towards a more market oriented economy, or will maintain its state-run system.

SOURCES

Chaudhry, Serena, “U.S. firms say Iraqi regulation a challenge to trade,” Reuters, 10/5/10

Department of Defense, “Measuring Stability and Security in Iraq June 2010,” 9/7/10

Razzouk, Nayla, “Iraq to Offer Tenders to Revamp 250 State Industrial Plants, Official Says,” Bloomberg, 9/28/10

Thursday, October 21, 2010

Sadr’s Decision To Support Maliki And Its Effects Within And Without Iraq

England’s Guardian newspaper had two stories on October 17, 2010 that tried to explain why Moqtada al-Sadr suddenly changed course and decided to support Nouri al-Maliki for a second term as prime minister. At first, the Sadrists were one of the greatest opponents to Maliki’s return. Sadr called the premier a liar and said he could not be trusted. Then suddenly on October 1, the Sadrists announced that they would back Maliki. The Guardian claimed this happened due to a concerted lobbying effort orchestrated by Iran, Maliki, Shiite clerics, Lebanon’s Hezbollah, and Syria.

The effort to change Sadr’s mind about Maliki started in September 2010. First, Ayatollah Kadem al-Hussein al-Haeri, Sadr’s mentor who lives in Iran, called on him to reconsider his position on the premiership. Next, Maliki sent a delegation to Qom, Iran made up of one of his top advisers Tariq Najm Abdullah and his chief of staff Abdul Halim al-Zuhairi to meet with Sadr. Also present were Iranian Revolutionary Guards Qods Force commander General Qassim Suleimani, who has long been in charge of Tehran’s Iraq policy, and the head of Hezbollah’s politburo Mohammed Kawatharani. Later in the month Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadenijad stopped in Syria on his way to give a speech at the United Nations to talk with President Bashar al-Assad. Assad had come out for Iyad Allawi and his Iraqi National Movement during the 2010 Iraqi elections, and even organized a meeting between Allawi and Sadr in Damascus in July. Ahmadenijad held a two-hour meeting trying to convince Assad of Maliki’s case, to get another voice to lobby Sadr. Moqtada was still not convinced however, and demanded consultations with Iran’s supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and Hezbollah’s chief Hassan Nasrallah. The latter demanded that Maliki promise to not let the U.S. military stay in Iraq after 2011, the deadline set in the Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) signed between Washington and Baghdad at the end of the Bush administration. Maliki allegedly conceded to not renew the SOFA in 2011. Both religious figures then advised Sadr to switch his support to Maliki. The Iraqi premier then sent chief of staff Zuhairi to Damascus to meet with President Assad at the Damascus airport to finally cement his backing. Finally, Maliki traveled to Syria on October 13 to meet with President Assad, and then headed off to Iran on October 18 where he met with President Ahmadenijad, Ayatollah Khamenei, Iranian Foreign Minister Manushaher Mottaki, and Vice President Rida Rahimi, along with Sadr in Qom, the first time the two had met face to face in five years. If the Guardian is right, it took this conglomeration of clerics and leaders to win over Sadr, and begin a regional movement in support of Maliki. That coalition now rivals Allawi’s foreign supporters in Saudi Arabia and Turkey, and swayed Syria away from aligning with them.

In return for his change of heart, Sadr is making some haughty demands. It’s been reported that they are asking for seven ministries, the secretary general of the cabinet, and deputy ministers in all the security agencies. They have also allegedly demanded 100,000 government jobs, and the release of all Sadrist prisoners. One movement leader even said that they deserved 25% of the staffing in each ministry. The movement is also acting so presumptious that it has turned the tide in forming a new ruling coalition, that it has begun posting flyers and banners of Sadr and his assassinated father Ayatollah Mohammed Sadiq al-Sadr in and around parliament.

Sadr’s decision has also set off counter moves by the White House. U.S. Ambassador to Iraq James Jeffrey told the press that if Sadr had a leading role in a new government that might jeopardize Washington-Baghdad ties. The Americans have also reportedly told the Kurds that they should withhold their support for Maliki to block Sadr’s ascendancy. Iraq’s politicians don’t need any encouragement to drag out negotiations. On the other hand, the Kurds are now in a very advantageous position as they are the largest uncommitted bloc left, and can largely determine who will be the next premier. Using that leverage may be more important than listening to the U.S. right now.

Maliki is also trying to capitalize upon the turn of events. Besides his trips to Syria and Iran, he also went to Jordan. There are also plans to go to Egypt and Turkey next. If he can’t convince them to back his drive for power directly, he’s likely asking them to talk with Allawi to give up his desire to return to power, and throw his list behind Maliki’s instead. He wants Tehran to sway the Supreme Islamic Iraqi Council (SIIC) to his side as well. The SIIC is making a last desperate attempt to remain relevant despite losing most of their popular support since the 2005 election, and have nominated current Vice President Adel Abdul Madhi for the premier as a result. Maliki feels that the tide has turned in his favor since Sadr came out for him. Like Tehran, the premier is now working on the regional front to solidify his position.

Iraq is still probably weeks and even months away from forming a new government. Sadr’s decision to come out for Maliki was one of the first major changes in the stalemate that has been going on since the March 2010 election. Tehran had a leading role in Sadr’s choice organizing Syria, Hezbollah, and Ayatollah Haeri to all lobby him. That shows Iran’s ability to shape events in the country. This set off a chain reaction both within and without Iraq. The U.S. is now alarmed that the anti-American Sadr will have a leading role in any new government, while Maliki is on a regional tour to drum up support. That just increases Sadr’s influence, since he can rightly believe that all this activity is due to his actions. He’s likely to get most of what he wants in a new government, since not only did he drag out talks with other parties to maximize his position, he also has a political movement and a militia that can exert his will after all the talks are over. It’s just the latest example of Sadr being a political survivor after many had discounted him when his movement fractured, Maliki went after his followers in 2008, he disbanded the Mahdi Army, and then his candidates didn’t fare as well as expected in the 2009 provincial vote. At the same time, he was in almost the exact same spot in 2006 when he put Maliki into office the first time. That relationship didn’t last, so it’s wrong to think that Moqtada has suddenly reached a new apex. Iraq’s politics are like a soap opera with drawn out relationships, backstabbing, and plenty of drama, so what’s happening now, can always change dramatically in the future.

SOURCES

AK News, “Sadr bloc staggers govt. formation in Iraq: source,” 4/21/10

Alsumaria, “Al Maliki meets Al Sadr in Iran,” 10/19/10

Aswat al-Iraq, “Iraqi PM arrives in Damascus,” 10/13/10

Chulov, Martin, “How Iran brokered a secret deal to put its ally in power in Iraq,” Guardian, 10/17/10

- “Iran brokers behind-the-scenes deal for pro-Tehran government in Iraq,” Guardian, 10/17/10

Dagher, Sam, “U.S. Envoy to Iraq Warns About Sadr’s Role,” Wall Street Journal, 10/5/10

England, Andrew, “Iraq PM attempts to woo rival’s backers,” Financial Times, 10/14/10

Erdbrink, Thomas and Fadel, Leila, “Maliki meets with Iranian leaders in Tehran,” Washington Post, 10/18/10

Hanna, Michael Wahid, “Iran Has Less Power in Iraq Than We Think,” Atlantic, 10/14/10

Leland, John, “Moktada, Moktada, Moktada,” At War, New York Times, 10/19/10

Myers, Steven Lee, “Sadr Calls for New Iraqi Government,” New York Times, 7/19/10

Sands, Phil, “Syria helps to break deadlock in Baghdad,” The National, 8/24/10

Sinaiee, Maryam and Theodoulou, Michael, “Iran trip bolsters Malikis credentials,” The National, 10/18/10

Sly, Liz, “U.S. now urges Iraqis to take their time in forming government,” Los Angeles Times, 10/18/10

Xinhua, “Neighbors wrestle for sway over Iraq following U.S. pullout,” 8/17/10

The effort to change Sadr’s mind about Maliki started in September 2010. First, Ayatollah Kadem al-Hussein al-Haeri, Sadr’s mentor who lives in Iran, called on him to reconsider his position on the premiership. Next, Maliki sent a delegation to Qom, Iran made up of one of his top advisers Tariq Najm Abdullah and his chief of staff Abdul Halim al-Zuhairi to meet with Sadr. Also present were Iranian Revolutionary Guards Qods Force commander General Qassim Suleimani, who has long been in charge of Tehran’s Iraq policy, and the head of Hezbollah’s politburo Mohammed Kawatharani. Later in the month Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadenijad stopped in Syria on his way to give a speech at the United Nations to talk with President Bashar al-Assad. Assad had come out for Iyad Allawi and his Iraqi National Movement during the 2010 Iraqi elections, and even organized a meeting between Allawi and Sadr in Damascus in July. Ahmadenijad held a two-hour meeting trying to convince Assad of Maliki’s case, to get another voice to lobby Sadr. Moqtada was still not convinced however, and demanded consultations with Iran’s supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and Hezbollah’s chief Hassan Nasrallah. The latter demanded that Maliki promise to not let the U.S. military stay in Iraq after 2011, the deadline set in the Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) signed between Washington and Baghdad at the end of the Bush administration. Maliki allegedly conceded to not renew the SOFA in 2011. Both religious figures then advised Sadr to switch his support to Maliki. The Iraqi premier then sent chief of staff Zuhairi to Damascus to meet with President Assad at the Damascus airport to finally cement his backing. Finally, Maliki traveled to Syria on October 13 to meet with President Assad, and then headed off to Iran on October 18 where he met with President Ahmadenijad, Ayatollah Khamenei, Iranian Foreign Minister Manushaher Mottaki, and Vice President Rida Rahimi, along with Sadr in Qom, the first time the two had met face to face in five years. If the Guardian is right, it took this conglomeration of clerics and leaders to win over Sadr, and begin a regional movement in support of Maliki. That coalition now rivals Allawi’s foreign supporters in Saudi Arabia and Turkey, and swayed Syria away from aligning with them.

A poster of Sadr on a checkpoint leading to the Iraqi parliament building

Source: New York Times

Source: New York Times

In return for his change of heart, Sadr is making some haughty demands. It’s been reported that they are asking for seven ministries, the secretary general of the cabinet, and deputy ministers in all the security agencies. They have also allegedly demanded 100,000 government jobs, and the release of all Sadrist prisoners. One movement leader even said that they deserved 25% of the staffing in each ministry. The movement is also acting so presumptious that it has turned the tide in forming a new ruling coalition, that it has begun posting flyers and banners of Sadr and his assassinated father Ayatollah Mohammed Sadiq al-Sadr in and around parliament.

Sadr’s decision has also set off counter moves by the White House. U.S. Ambassador to Iraq James Jeffrey told the press that if Sadr had a leading role in a new government that might jeopardize Washington-Baghdad ties. The Americans have also reportedly told the Kurds that they should withhold their support for Maliki to block Sadr’s ascendancy. Iraq’s politicians don’t need any encouragement to drag out negotiations. On the other hand, the Kurds are now in a very advantageous position as they are the largest uncommitted bloc left, and can largely determine who will be the next premier. Using that leverage may be more important than listening to the U.S. right now.

Maliki is also trying to capitalize upon the turn of events. Besides his trips to Syria and Iran, he also went to Jordan. There are also plans to go to Egypt and Turkey next. If he can’t convince them to back his drive for power directly, he’s likely asking them to talk with Allawi to give up his desire to return to power, and throw his list behind Maliki’s instead. He wants Tehran to sway the Supreme Islamic Iraqi Council (SIIC) to his side as well. The SIIC is making a last desperate attempt to remain relevant despite losing most of their popular support since the 2005 election, and have nominated current Vice President Adel Abdul Madhi for the premier as a result. Maliki feels that the tide has turned in his favor since Sadr came out for him. Like Tehran, the premier is now working on the regional front to solidify his position.

Iraq is still probably weeks and even months away from forming a new government. Sadr’s decision to come out for Maliki was one of the first major changes in the stalemate that has been going on since the March 2010 election. Tehran had a leading role in Sadr’s choice organizing Syria, Hezbollah, and Ayatollah Haeri to all lobby him. That shows Iran’s ability to shape events in the country. This set off a chain reaction both within and without Iraq. The U.S. is now alarmed that the anti-American Sadr will have a leading role in any new government, while Maliki is on a regional tour to drum up support. That just increases Sadr’s influence, since he can rightly believe that all this activity is due to his actions. He’s likely to get most of what he wants in a new government, since not only did he drag out talks with other parties to maximize his position, he also has a political movement and a militia that can exert his will after all the talks are over. It’s just the latest example of Sadr being a political survivor after many had discounted him when his movement fractured, Maliki went after his followers in 2008, he disbanded the Mahdi Army, and then his candidates didn’t fare as well as expected in the 2009 provincial vote. At the same time, he was in almost the exact same spot in 2006 when he put Maliki into office the first time. That relationship didn’t last, so it’s wrong to think that Moqtada has suddenly reached a new apex. Iraq’s politics are like a soap opera with drawn out relationships, backstabbing, and plenty of drama, so what’s happening now, can always change dramatically in the future.

SOURCES

AK News, “Sadr bloc staggers govt. formation in Iraq: source,” 4/21/10

Alsumaria, “Al Maliki meets Al Sadr in Iran,” 10/19/10

Aswat al-Iraq, “Iraqi PM arrives in Damascus,” 10/13/10

Chulov, Martin, “How Iran brokered a secret deal to put its ally in power in Iraq,” Guardian, 10/17/10

- “Iran brokers behind-the-scenes deal for pro-Tehran government in Iraq,” Guardian, 10/17/10

Dagher, Sam, “U.S. Envoy to Iraq Warns About Sadr’s Role,” Wall Street Journal, 10/5/10

England, Andrew, “Iraq PM attempts to woo rival’s backers,” Financial Times, 10/14/10

Erdbrink, Thomas and Fadel, Leila, “Maliki meets with Iranian leaders in Tehran,” Washington Post, 10/18/10

Hanna, Michael Wahid, “Iran Has Less Power in Iraq Than We Think,” Atlantic, 10/14/10

Leland, John, “Moktada, Moktada, Moktada,” At War, New York Times, 10/19/10

Myers, Steven Lee, “Sadr Calls for New Iraqi Government,” New York Times, 7/19/10

Sands, Phil, “Syria helps to break deadlock in Baghdad,” The National, 8/24/10

Sinaiee, Maryam and Theodoulou, Michael, “Iran trip bolsters Malikis credentials,” The National, 10/18/10

Sly, Liz, “U.S. now urges Iraqis to take their time in forming government,” Los Angeles Times, 10/18/10

Xinhua, “Neighbors wrestle for sway over Iraq following U.S. pullout,” 8/17/10

Anbar Holds Protest Over Akkas Gas Auction

On October 20, 2010 the Akkas natural gas field in Anbar province was successfully bid on. The winner was a consortium of South Korea’s KOGAS and Kazakhstan’s KazMunai Gas. As reported before, Anbar’s governor and provincial council objected to the auction, claiming that the field should be under local rather than federal control. Anbar’s politicians organized a demonstration in Ramadi, the provincial capital, the day of the auction. Protestors demanded that the foreign companies hire workers from the province as well.

SOURCE

Reuters, “Residents chant slogans of Baghdad,” 10/20/10

Salaheddin, Sinan, “Iraq gas auction fizzles despite hopes,” Associated Press, 10/20/10

SOURCE

Reuters, “Residents chant slogans of Baghdad,” 10/20/10

Salaheddin, Sinan, “Iraq gas auction fizzles despite hopes,” Associated Press, 10/20/10

Wednesday, October 20, 2010

Iraq To Hold Natural Gas Auction Today

Today, October 20, 2010, Iraq’s Oil Ministry will auction off three natural gas fields. They have a combined estimated reserve of 11.2 trillion cubic feet of gas, 10% of Iraq’s total. There are major questions about whether this will be a successful process or not.

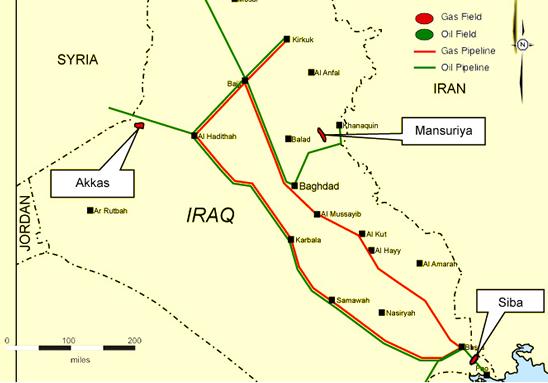

The three fields involved in the auction are Akkas, Siba, and Mansuriyah. Akkas is in Anbar by Syria with a reserve of 5.6 trillion cubic feet. Mansuriyah is in Diyala near the Iranian border with a reserve of 5.6 trillion cubic feet. Finally, Siba is in Basra with a reserve of 1.1 trillion cubic feet.

The Oil Ministry has been worried about the level of interest international energy firms have expressed in the auction. The event was first set for September 1, then pushed back to October 1, and then finally October 24. Each time the Ministry said that it was trying to get more companies involved. Iraq has also lessened its terms. It dropped a requirement that businesses find an export partner for half of the gas they produced, it cut the large signature bonuses corporations will have to pay, and reduced fees to train Iraqis in the industry that were going to run $1-$5 million per year. To sweeten the deals even more, Baghdad said that it will pay the companies whether the gas they produced is used or not, and will revise the money the government will pay for added production at each field. One energy analyst said Iraq might have to offer even more, like equity that will allow firms to count the reserves in each field on their own books. Overall, the gas deals are similar to the oil ones offered in 2009. Companies will be offered 20-year service contracts where they will be paid a flat fee for their service, and then an additional amount once they reach a set production level.

There are many reasons why Iraq has had problems with this auction. The Oil Ministry said it wants to use the gas for domestic use first. The Ministry has estimated that the nation’s power stations and businesses need an average of 1.05 billion cubic feet of gas per day, and that would increase to 5 billion by 2018. Right now they only receive 670 million cubic feet per day. Iraq lacks storage facilities or pipelines to handle any new production however. The government said it would construct this network, but it would not be ready until 2014. The lack of infrastructure also includes exports. Akkas and Siba for example, are just along the Syrian and Kuwaiti borders respectively, but there’s no way to sell any gas there as there are no lines connecting the countries. As reported before, the Anbar provincial government also came out against the auction of the Akkas field and any foreign sales from there. Mansuriyah is near Iran, but foreign corporations are probably unwilling to sell there because of international sanctions. Gas is also harder to sell then oil. Right now there is a surplus of the commodity on the world market, and there are other countries that offer better deals and more safety than Iraq. Analysts have said that the sale of gas requires long-term agreements, but none exist. Next, the companies will be selling gas to the Oil Ministry, and they have not set a price. That may determine whether any profits are made. Finally, there have been reports that Baghdad has no plans for who or how the gas will be used. It wants to develop the industry, attract foreign investment, and power their factories, but without a strategy these endeavors may prove fruitless for both Iraq and the companies.

Because of these issues, only 13 of 45 pre-qualified corporations have registered and paid fees to participate in today’s auction. Those are France’s Total, Italy’s Eni, Edison, Norway’s Statoil, Kazakhstan’s KazMunai Gas, Turkey’s TPAO, Japan’s Oil, Gas and Metals National Corporation, Itochu Corp., Mitsubishi, Kuwait Energy, India’s Oil and Natural Gas Corp., South Korea’s KOGAS, TNK-BP, and BP PLC’s Russian joint venture. Back in 2009 the Akkas and Mansuriyah fields were unsuccessfully offered as part of the first oil bidding round, but only Akkas got any interest. A consortium of Edison, Malaysia’s Petronas, China’s CNPC, Turkey’s TPAO, and Korea’s KOGAS offered $38 for each additional amount of gas produced after production levels were reached, while the Oil Ministry countered with $8.50. Today will see whether Iraq does any better.

SOURCES

El Gamal, Rania, “PREVIEW-Iraq to auction gas fields despite uncertainties,” Reuters, 10/19/10

Hoyos, Carola, Warrell, Helen, and Bernard, Steve, “Crude Competition,” Financial Times, 6/30/09

Salaheddin, Sinan, “Iraq gas auction draws limited participation,” Associated Press, 10/19/10

The three fields involved in the auction are Akkas, Siba, and Mansuriyah. Akkas is in Anbar by Syria with a reserve of 5.6 trillion cubic feet. Mansuriyah is in Diyala near the Iranian border with a reserve of 5.6 trillion cubic feet. Finally, Siba is in Basra with a reserve of 1.1 trillion cubic feet.

The Oil Ministry has been worried about the level of interest international energy firms have expressed in the auction. The event was first set for September 1, then pushed back to October 1, and then finally October 24. Each time the Ministry said that it was trying to get more companies involved. Iraq has also lessened its terms. It dropped a requirement that businesses find an export partner for half of the gas they produced, it cut the large signature bonuses corporations will have to pay, and reduced fees to train Iraqis in the industry that were going to run $1-$5 million per year. To sweeten the deals even more, Baghdad said that it will pay the companies whether the gas they produced is used or not, and will revise the money the government will pay for added production at each field. One energy analyst said Iraq might have to offer even more, like equity that will allow firms to count the reserves in each field on their own books. Overall, the gas deals are similar to the oil ones offered in 2009. Companies will be offered 20-year service contracts where they will be paid a flat fee for their service, and then an additional amount once they reach a set production level.

There are many reasons why Iraq has had problems with this auction. The Oil Ministry said it wants to use the gas for domestic use first. The Ministry has estimated that the nation’s power stations and businesses need an average of 1.05 billion cubic feet of gas per day, and that would increase to 5 billion by 2018. Right now they only receive 670 million cubic feet per day. Iraq lacks storage facilities or pipelines to handle any new production however. The government said it would construct this network, but it would not be ready until 2014. The lack of infrastructure also includes exports. Akkas and Siba for example, are just along the Syrian and Kuwaiti borders respectively, but there’s no way to sell any gas there as there are no lines connecting the countries. As reported before, the Anbar provincial government also came out against the auction of the Akkas field and any foreign sales from there. Mansuriyah is near Iran, but foreign corporations are probably unwilling to sell there because of international sanctions. Gas is also harder to sell then oil. Right now there is a surplus of the commodity on the world market, and there are other countries that offer better deals and more safety than Iraq. Analysts have said that the sale of gas requires long-term agreements, but none exist. Next, the companies will be selling gas to the Oil Ministry, and they have not set a price. That may determine whether any profits are made. Finally, there have been reports that Baghdad has no plans for who or how the gas will be used. It wants to develop the industry, attract foreign investment, and power their factories, but without a strategy these endeavors may prove fruitless for both Iraq and the companies.

Because of these issues, only 13 of 45 pre-qualified corporations have registered and paid fees to participate in today’s auction. Those are France’s Total, Italy’s Eni, Edison, Norway’s Statoil, Kazakhstan’s KazMunai Gas, Turkey’s TPAO, Japan’s Oil, Gas and Metals National Corporation, Itochu Corp., Mitsubishi, Kuwait Energy, India’s Oil and Natural Gas Corp., South Korea’s KOGAS, TNK-BP, and BP PLC’s Russian joint venture. Back in 2009 the Akkas and Mansuriyah fields were unsuccessfully offered as part of the first oil bidding round, but only Akkas got any interest. A consortium of Edison, Malaysia’s Petronas, China’s CNPC, Turkey’s TPAO, and Korea’s KOGAS offered $38 for each additional amount of gas produced after production levels were reached, while the Oil Ministry countered with $8.50. Today will see whether Iraq does any better.

SOURCES

El Gamal, Rania, “PREVIEW-Iraq to auction gas fields despite uncertainties,” Reuters, 10/19/10

Hoyos, Carola, Warrell, Helen, and Bernard, Steve, “Crude Competition,” Financial Times, 6/30/09

Salaheddin, Sinan, “Iraq gas auction draws limited participation,” Associated Press, 10/19/10

Tuesday, October 19, 2010

Anbar Objects To Iraq’s October Natural Gas Auction

Map of the 3 natural gas fields to be auctioned off Oct. 20, 2010

Source: Energy-Pedia News

Source: Energy-Pedia News

On October 20, 2010 Iraq’s Oil Ministry will hold an auction for three natural gas fields. One of them is Akkas in Anbar province. There the governor and provincial council are demanding that they, and not Baghdad be in charge of developing the field.

Anbar’s governor and the head of the provincial council both talked with Reuters recently to voice their objections to the Oil Ministry’s plans. Governor Qasim Abdi Muhammad Hammadi al Fahadawi said he was against any government deal for Akkas. He claimed the field should be under local control instead. He warned that the province would not provide any security for Akkas if it was auctioned off. The head of the provincial council also said that Baghdad had ignored Anbar’s natural resources, and that the Oil Ministry should start exploring for gas and oil there.

Akkas has an estimated 5.6 trillion cubic feet of gas reserves. It, along with Mansuriya in Diyala, and Siba in Basra, are going to be bid on by thirteen international companies tomorrow. Originally, the auction was supposed to occur on September 1, but was then delayed until October 1 to try to draw up more interest. It was set back again until October 24 because the Ministry claimed several companies had asked for additional information on the process. Some of the businesses that have paid fees to participate are Italy’s Edison, France’s Total, South Korea’s KOGAS, and Russia’s TNK-BP.

Anbar’s objections are just the latest example of a province calling for greater control over its resources. The Oil Ministry however, clams that it has the ultimate authority over developing the country’s petroleum and gas, and has done little to appease local concerns. That could lead to problems between the central and provincial governments if Akkas is successfully bid on. At the same time, the Oil Ministry doesn’t rely upon the governorates to manage and export resources so Anbar is limited in what it can do about the gas auction.

SOURCES